---

{

title: "Rules of React's useEffect",

description: "useEffect is prolific in React apps. Here are four rules associated with the hook and in-depth explanations of why they're important.",

published: '2022-02-22T22:12:03.284Z',

authors: ['crutchcorn'],

tags: ['react', 'javascript'],

attached: [],

license: 'coderpad',

originalLink: 'https://coderpad.io/blog/development/rules-of-reacts-useeffect/'

}

---

React’s `useEffect` is a powerful API with lots of capabilities, and therefore flexibility. Unfortunately, this flexibility often leads to abuse and misuse, which can greatly damage an app’s stability.

The good news is that if you follow a set of rules designated to protect you during coding, your application can be secure and performant.

No, we’re not talking about React’s “[Rules of Hooks](https://reactjs.org/docs/hooks-rules.html)”, which includes rules such as:

- No conditionally calling hooks

- Only calling hooks inside of hooks or component

- Always having items inside of the dependency array

These rules are good, but can be detected automatically with linting rules. It's good that they're there (and maintained by Meta), but overall, we can pretend like everyone has them fixed because their IDE should throw a warning.

Specifically, I want to talk about the rules that can only be caught during manual code review processes:

- Keep all side effects inside `useEffect`

- Properly clean up side effects

- Don't use `ref` in `useEffect`

- Don't use `[]` as a guarantee that something only happens once

While these rules may seem obvious at first, we'll be taking a deep dive into the "why" of each. As a result, you may learn something about how React works under the hood - even if you're a React pro.

## Keep all side effects inside `useEffect`

For anyone familiar with React’s docs, you’ll know that this rule has been repeated over and over again. But why? Why is this a rule?

After all, what would prevent you from storing logic inside of a `useMemo` and simply having an empty dependency array to prevent it from running more than once?

Let’s try that out by running a network request inside of a `useMemo`:

```jsx

const EffectComp = () => {

const [activity, setActivity] = React.useState(null);

const effectFn = React.useMemo(() => {

// Make a network request here

fetch("https://www.boredapi.com/api/activity")

.then(res => res.json())

.then(res => setActivity(res.activity));

}, [])

return

{activity}

}

```

Huh. It works first try without any immediately noticeable downsides. This works because `fetch` is asynchronous, meaning that it doesn’t block the [event loop](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8aGhZQkoFbQ&vl=en). Instead, let’s change that code to be a synchronous `XHR` request and see if that works too.

```

function getActivity() {

var request = new XMLHttpRequest();

request.open('GET', 'https://www.boredapi.com/api/activity', false); // `false` makes the request synchronous

request.send(null);

return JSON.parse(request.responseText);

}

const EffectComp = () => {

const [data, setData] = React.useState(null);

const effectFn = React.useMemo(() => {

setData(getActivity().activity);

}, []);

return

Hello, world! {data}

;

}

```

Here, we can see behavior that we might not expect to see. When using useMemo alongside a blocking method, the entire screen will halt before drawing anything. The initial paint is then made after the fetch is finally finished.

However, if we use useEffect instead, this does not occur.

Here, we can see the initial paint occur, drawing the “Hello” message before the blocking network call is made.

Why does this happen?

### Understanding hook lifecycles

The reason `useEffect` is still able to paint but useMemo cannot is because of the timings of each of these hooks. You can think of `useMemo` as occurring right in line with the rest of your render code.

In terms of timings, the two pieces of code are very similar:

```jsx

const EffectComp = () => {

const [data, setData] = React.useState(null);

const effectFn = React.useMemo(() => {

setData(getActivity().activity);

}, []);

return

;

}

```

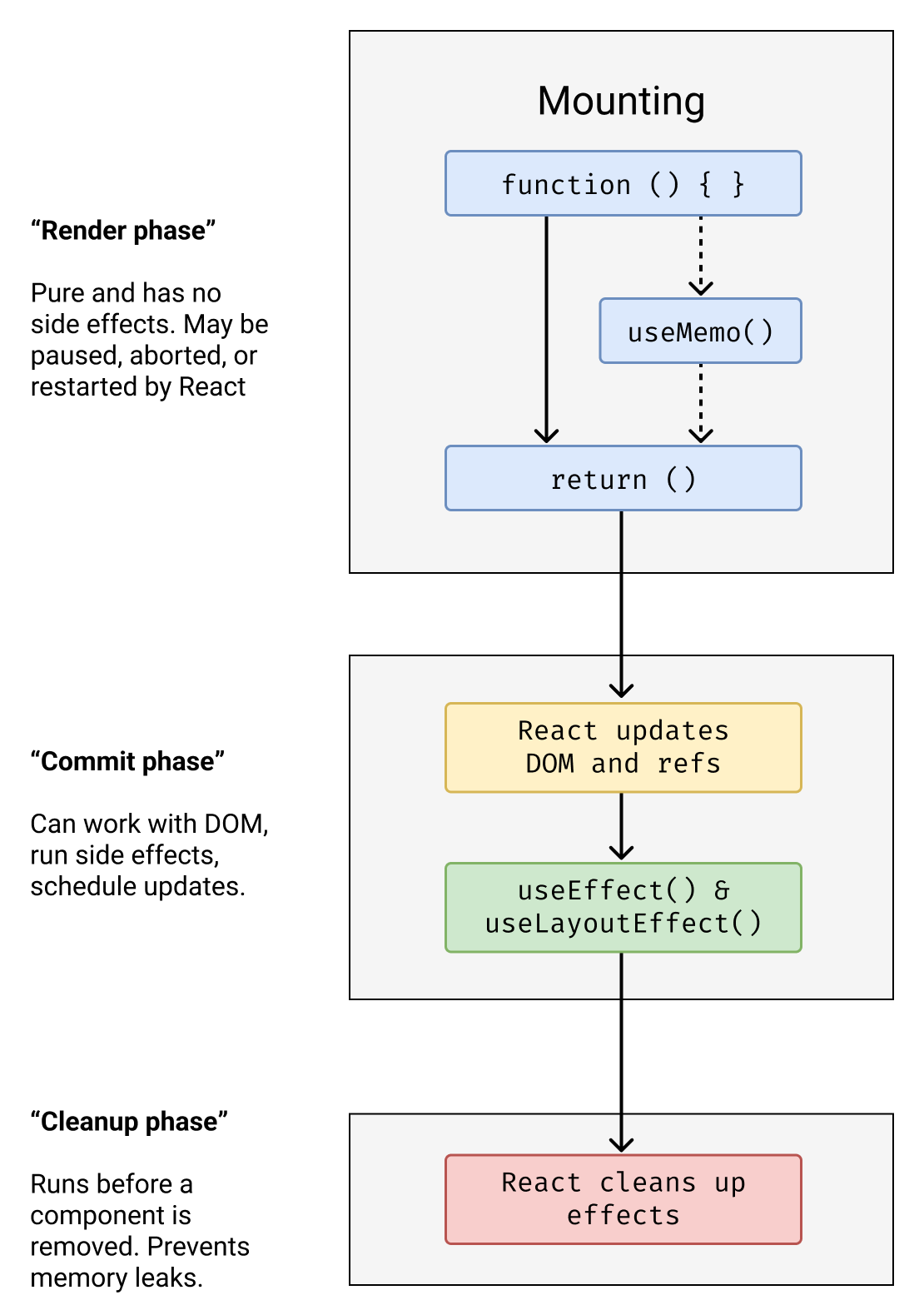

This inlining behavior occurs because `useMemo` runs during the “render” phase of a component. `useEffect`, on the other hand, runs **after** a component renders out, which allows an initial render before the blocking behavior halts things for us.

Those among you that know of “useLayoutEffect” may think you have found a gotcha in what I just said.

“Ahh, but wouldn’t useLayoutEffect also prevent the browser from drawing until the network call is completed?”

Not quite! You see, while useMemo runs during the render phase, useLayoutEffect runs during the “*commit”* phase and therefore renders the initial contents to screen first.

> [useLayoutEffect’s signature is identical to useEffect, but it fires synchronously after all DOM mutations.](https://reactjs.org/docs/hooks-reference.html#uselayouteffect)

See, the commit phase is the part of a component’s lifecycle *after* React is done asking all the components what they want the UI to look like, has done all the diffing, and is ready to update the DOM.

> If you’d like to learn more about how React does its UI diffing and what this process all looks like under the hood, take a look at [Dan Abramov’s wonderful “React as a UI Runtime” post](https://overreacted.io/react-as-a-ui-runtime/).

>

> There’s also [this awesome chart demonstrating how all of the hooks tie in together](https://github.com/Wavez/react-hooks-lifecycle) that our chart is a simplified version of.

Now, this isn’t to say that you should optimize your code to work effectively with blocking network calls. After all, while `useEffect` allows you to render your code, a blocking network request still puts you in the uncomfortable position of your user being unable to interact with your page.

Because JavaScript is single-threaded, a blocking function will prevent user interaction from being processed in the event loop.

> If you read the last sentence and are scratching your head, you’re not alone. The idea of JavaScript being single-threaded, what an “event loop” is, and what “blocking” means are all quite confusing at first.

>

> We suggest taking a look at [this great explainer talk from Philip Robers](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8aGhZQkoFbQ) to understand more.

That said, this isn’t the only scenario where the differences between `useMemo` and `useEffect` cause misbehavior with side effects. Effectively, they’re two different tools with different usages and attempting to merge them often breaks things.

Attempting to use `useMemo` in place of `useEffect` leads to scenarios that can introduce bugs, and it may not be obvious what’s going wrong at first. After long enough, with enough of these floating about in your application, it’s sort of “death by a thousand paper-cuts”.

These papercuts aren't the only problem, however. After all, the APIs for useEffect and useMemo are not the same. This incongruity between APIs is especially pronounced for network requests because a key feature is missing from the `useMemo` API: effect cleanup.

## Always clean up your side effects

Occasionally, when using `useEffect`, you may be left with something that requires cleanup. A classic example of this might be a network call.

Say you have an application to give bored users an activity to do at home. Let’s use a network request that retrieves an activity from an API:

```jsx

const EffectComp = () => {

const [activity, setActivity] = React.useState(null);

React.useEffect(() => {

fetch("https://www.boredapi.com/api/activity")

.then(res => res.json())

.then(res => setActivity(res.activity));

}, [])

return

{activity}

}

```

While this works for a single activity, what happens when the user completes the activity?

Let’s give them a button to rotate between new activities and include a count of how many times the user has requested an activity.

```jsx

const EffectComp = () => {

const [activity, setActivity] = React.useState(null);

const [num, setNum] = React.useState(1);

React.useEffect(() => {

// Make a network request here

fetch("https://www.boredapi.com/api/activity")

.then(res => res.json())

.then(res => setActivity(res.activity));

// Re-run this effect when `num` is updated during render

}, [num])

return (

You should: {activity}

You have done {num} activities

)

}

```

Just as we intended, we get a new network activity if we press the button. We can even press the button multiple times to get a new activity per press.

But wait, what happens if we slow down our network speed and press the “request” button rapidly?

Oh no! Even tho we’ve stopped clicking the button, our network requests are still coming in. This gives us a sluggish feeling experience, especially when latency times between network calls are high.

Well, this is where our cleanup would come into effect. Let’s add an [AbortSignal](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/AbortSignal) to cancel a request when we request a new one.

```jsx

const EffectComp = () => {

const [activity, setActivity] = React.useState(null);

const [num, setNum] = React.useState(1);

React.useEffect(() => {

const controller = new AbortController();

const signal = controller.signal;

// Make a network request here

fetch("https://www.boredapi.com/api/activity", {signal})

.then(res => res.json())

.then(res => setActivity(res.activity));

return () => {

controller.abort();

}

// Re-run this effect when `num` is updated during render

}, [num])

return (

You should: {activity}

You have done {num} activities

)

}

```

If we open our network request tab, you’ll notice how our network calls are now being canceled when we initialize a new one.

This is a good thing! It means that instead of a jarring experience of jumpiness, you’ll now only see a single activity after the end of a chain of clicking.

While this may seem like a one-off that we created ourselves using artificial network slowdowns, this is the real-world experience users on slow networks may experience!

What’s more, when you consider API timing differences, this problem may be even more widespread.

Let’s say that you’re using a [new React concurrent feature](https://coderpad.io/blog/why-react-18-broke-your-app/), which may cause an interrupted render, forcing a new network call before the other has finished.

The first call hangs on the server for slightly longer for whatever reason and takes 500ms, but the second call goes through immediately in 20ms. But oh no, during that 480ms there was a change in the data!

This means that our `.then` which runs `setActivity` will execute on the first network call – complete with stale data (showing “10,000”) – **after** the second network call.

This is important to catch early, because these shifts in behavior can be immediately noticeable to a user when it happens. These issues are also often particularly difficult to find and work through after the fact.

## Don’t use refs in useEffect

If you’ve ever used a useEffect to apply an `addEventListener`, you may have written something like the following:

```jsx

const RefEffectComp = () => {

const buttonRef = React.useRef();

const [count, setCount] = React.useState(0);

React.useEffect(() => {

function buttonAdder() {

setCount(v => v + 1);

}

buttonRef.current.addEventListener('click', buttonAdder);

return () => {

buttonRef.current.removeEventListener('click', buttonAdder);

}

}, [buttonRef.current])

return

{count}

}

```

While this might make intuitive sense due to utilizing `useEffect`’s cleanup, this code is actually not correct. You should not utilize a `ref` or `ref.current` inside of a dependency array for a hook.

This is because **changing refs does not force a re-render and therefore useEffect never runs when the value changes.**

While most assume that `useEffect` “listens” for changes in this array and runs the effect when it changes, this is an inaccurate mental model.

A more apt mental model might be: “useEffect only runs at most once per render. However, as an optimization, I can pass an array to prevent the side effect from running if the variable references inside of the array have not changed.”

This shift in understanding is important because the first version can easily lead to bugs in your app. For example, instead of rendering out the button immediately, let’s say that we need to defer the rendering for some reason.

Simple enough, we’ll add a `setTimeout` and a boolean to render the button.

```jsx

const RefEffectComp = ()=>{

const buttonRef = React.useRef();

const [count, setCount] = React.useState(0);

React.useEffect(() => {

function buttonAdder() {

setCount(v => v + 1);

}

console.log('UseEffect has run');

// This will throw an error during the first render otherwise

if (!buttonRef.current) return;

buttonRef.current.addEventListener('click', buttonAdder);

return () => {

buttonRef.current.removeEventListener('click', buttonAdder);

}

}, [buttonRef.current])

const [shouldRender, setShouldRender] = React.useState(false);

React.useEffect(() => {

const timer = setTimeout(() => {

setShouldRender(true);

}, 1000);

return () => {

clearTimeout(timer);

setShouldRender(false);

}

}, []);

return

{count}

{shouldRender && }

}

```

Now, if we wait a second for the button to render and click it, our counter doesn’t go up!

This is because once our `ref` is set after the initial render, it doesn’t trigger a re-render and our `useEffect` never runs.

A better way to write this would be to utilize a [“callback ref”](https://unicorn-utterances.com/posts/react-refs-complete-story#callback-refs), and then use a `useState` to force a re-render when it’s set.

```jsx

const RefEffectComp = ()=>{

const [buttonEl, setButtonEl] = React.useState();

const [count, setCount] = React.useState(0);

React.useEffect(() => {

function buttonAdder() {

setCount(v => v + 1);

}

if (!buttonEl) return;

buttonEl.addEventListener('click', buttonAdder);

return () => {

buttonEl.removeEventListener('click', buttonAdder);

}

}, [buttonEl])

const [shouldRender, setShouldRender] = React.useState(false);

React.useEffect(() => {

const timer = setTimeout(() => {

setShouldRender(true);

}, 1000);

return () => {

clearTimeout(timer);

setShouldRender(false);

}

}, []);

return

{count}

{shouldRender && }

}

```

This will force the re-render when `ref` is set after the initial render and, in turn, cause the `useEffect` to trigger as expected.

To be fair, this “rule” is more of a soft rule than anything. There are absolutely instances - such as setTimeout timers - where utilizing a ref inside of a useEffect make sense. Just make sure you have a proper mental model about refs and useEffect and you’ll be fine.

> Want to refine your understanding of refs even further? [See my article outlining the important details of refs for more.](https://unicorn-utterances.com/posts/react-refs-complete-story)

## Don’t expect an empty dependency array to only run once

While previous versions of React allowed you to utilize an empty array to guarantee that a `useEffect` would only run once, [React 18 changed this behavior](https://coderpad.io/blog/why-react-18-broke-your-app/). As a result, now `useEffect` may run any number of times when an empty dependency array passes, in particular when a [concurrent feature is utilized](https://github.com/reactwg/react-18/discussions/46#discussioncomment-846786).

Concurrent features are new to React 18 and allow React to pause, halt, and remount a component whenever React sees it appropriate.

As a result, this may break various aspects of your code.

You can [read more about how an empty dependency array can break in your app from our article about React 18’s changes to mounting.](https://coderpad.io/blog/why-react-18-broke-your-app/)

## Conclusion

React’s useEffect is an instrumental part of modern React applications. Now that you know more about its internals and the rules around it, you can build stronger and more dynamic programs!

If you want to continue learning skills that will help make your React apps better, I suggest taking a look at [our guide to React Unidirectionality](https://coderpad.io/blog/master-react-unidirectional-data-flow/), which outlines a good way to keep your application flow more organized.